Before we get to adding an initial set of users, we need to discuss how you manage users now and whether you want to integrate that with what you’re doing in Cloud Identity.

There are two main concepts that come into play here:

- The one source of truth for user identities. This is where you create and manage users and where you store information about those users (such as name, email, manager, and group membership).

- The Identity Provider (IdP) where you perform authentication to verify that a user is who they claim to be.

So, the big questions are, what are you going to use as the one source of truth for users? What are you going to use as an IdP? And if they aren’t the same, how are you going to mix them?

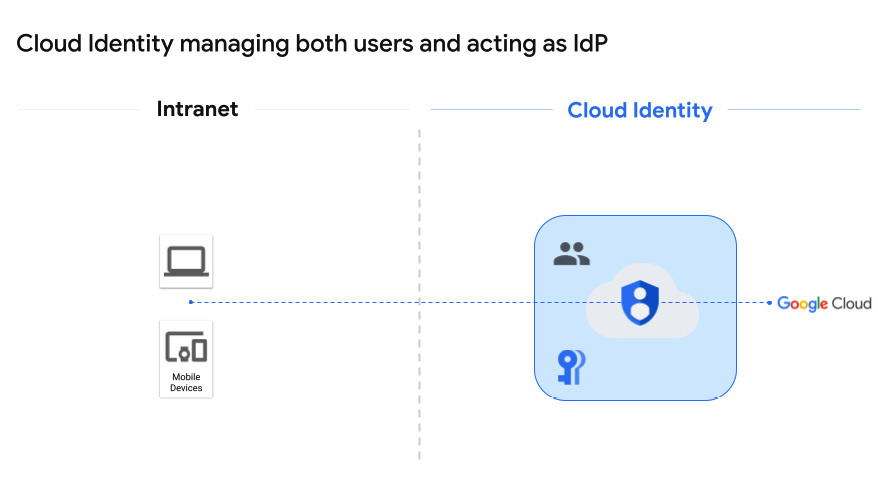

Cloud Identity managing users and acting as IdP

Let’s start with the case where Google Cloud Identity is managing both users and serving as an IdP, something like this:

Figure 2.3 – Cloud Identity managing both users and the IdP

The nice thing about this approach is that it’s easy, low-cost, and you don’t have to do anything to integrate Google Cloud Identity with an external IdP or user service. You are essentially setting up a new and isolated set of users, and you’re using a Google mission-critical security system to do it.

This is when you should use it:

- You’re just getting started as a new business, and leveraging Cloud Identity as both a user store and IdP just makes sense. In this case, I’d strongly consider Google Workspace as well, since it does such a nice job with Docs, Sheets, Drive, and so on.

- You are already using Google Workspace and simply want to add Google Cloud access.

- You want a small, isolated set of users to have access to Google Cloud services and you like the idea that they are managed independently in GCP.

This is what the login process will look like to a user:

- The user follows a link to a protected resource in GCP, such as Cloud Storage.

- If their browser isn’t already authenticated, then they are redirected to a standard Google sign-in screen where they enter their username and password. If 2SV is enabled, they are prompted to provide their key or code.

- If the user authenticates, then IAM decides whether they are authorized to access the requested resource, and if so, they are then redirected back to the service they requested – in our example, Cloud Storage.

That’s really easy, but what if an organization likes Google as an IdP but they are already managing users with a system in HR? In that case, a better option might be to split the duties.

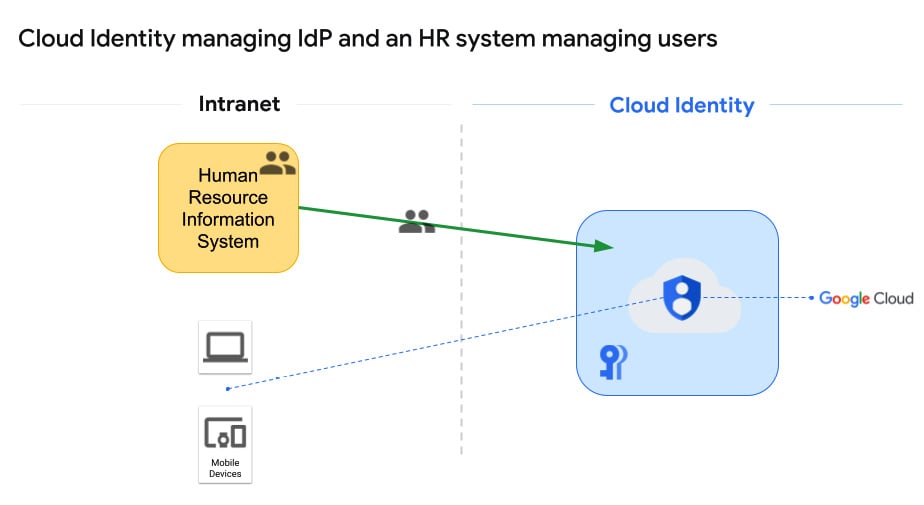

Cloud Identity managing IdP and an HR system managing users

Some organizations use a Human Resources Information System (HRIS) such as SAP SuccessFactors, BambooHR, Namely, Ultimate Software, or Workday to manage their users. By letting the HRIS focus on user management, you can preserve existing HR workflows for things such as provisioning new users, and Cloud Identity can be used to handle everything IdP-related. This architecture would look something like this:

Figure 2.4 – HRIS manages users and Google handles IdP

This configuration allows the HRIS system to focus on what it’s good at, HR, and lets Google handle something it’s good at, high-grade user authentication. The biggest downside here would be that if your HRIS can also manage passwords, you aren’t necessarily leveraging that. For some environments, that would imply that you have the same username in two systems, the HRIS and Cloud Identity, but the passwords wouldn’t be the same. You’d log into local intranet systems through the HRIS and to Google Cloud through Google. It’s either that or, more likely, you would make Google the only IdP, and your local systems would reach out to Google when logging into anything.

Here’s a good link to check on the detail of setting this stuff up: https://support.google.com/a/topic/7556794.

This is when you should use it:

- You already have a solid HRIS in place and would like to preserve your HR system workflows as you move to Google Cloud.

- You’re okay, and maybe even happy, to let Google handle the IdP, and have a plan to make Cloud Identity the only IdP for all in-and-out of cloud authentication – possibly because of the following point…

- There may be no existing centralized, on-premises IdP, and this gives you the chance to implement one.

This is what the login process will look like to a user (unchanged):

- The user follows a link to a protected resource, such as Google Cloud Storage.

- If their browser isn’t already authenticated, then they are redirected to a standard Google sign-in screen where they enter their username and password. If 2SV is enabled, they are prompted to provide their key or code.

- If the user authenticates, then IAM decides whether they are authorized to access the requested resource, and if so, they are then redirected back to the service they requested – in our example, Cloud Storage.

As I mentioned, one of the downsides with this approach is that some HRISs, as well as a bunch of other third-party apps such as AD, can manage both users and identities. What if we want to integrate one of those third-party services into Google Cloud? Well, there are several ways we can go about it.

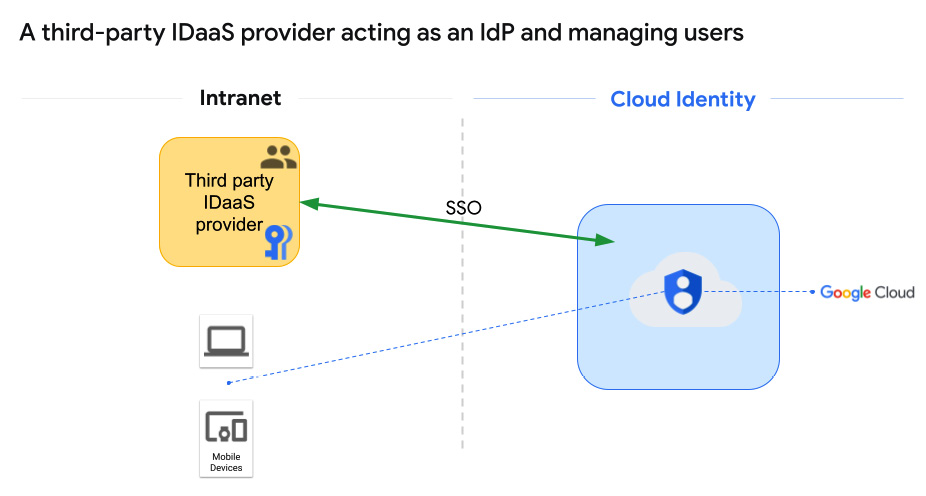

Cloud Identity delegates all IdP and user management to an external (non-AD) provider

The phrase we’re looking for here is: IDaaS provider. IDaaS providers range from specialized options, such as Okta or Ping, to some of the HRIS systems we discussed in the last section, such as SAP SuccessFactors or Workday, which can manage HR but also have components designed to handle IDaaS. Many of these Single Sign-On (SSO) services operate using an Extensible Markup Language (XML) standard called Security Assertion Markup Language (SAML), as shown in the following figure:

Figure 2.5 – A third-party IDaaS provider acting as an IdP and managing users

You know, I spent 4 years in the Marines, and I can tell you without any hesitation – the military has nothing on technology when it comes to acronyms.

For information on setting this option up, check out this link: https://support.google.com/cloudidentity/topic/7558767.

This is when you should use it:

- You already have an existing IDaaS provider with a set of users, and you don’t want to reinvent the user management or authentication wheel.

- You don’t need or want to synchronize passwords or other credentials with Google.

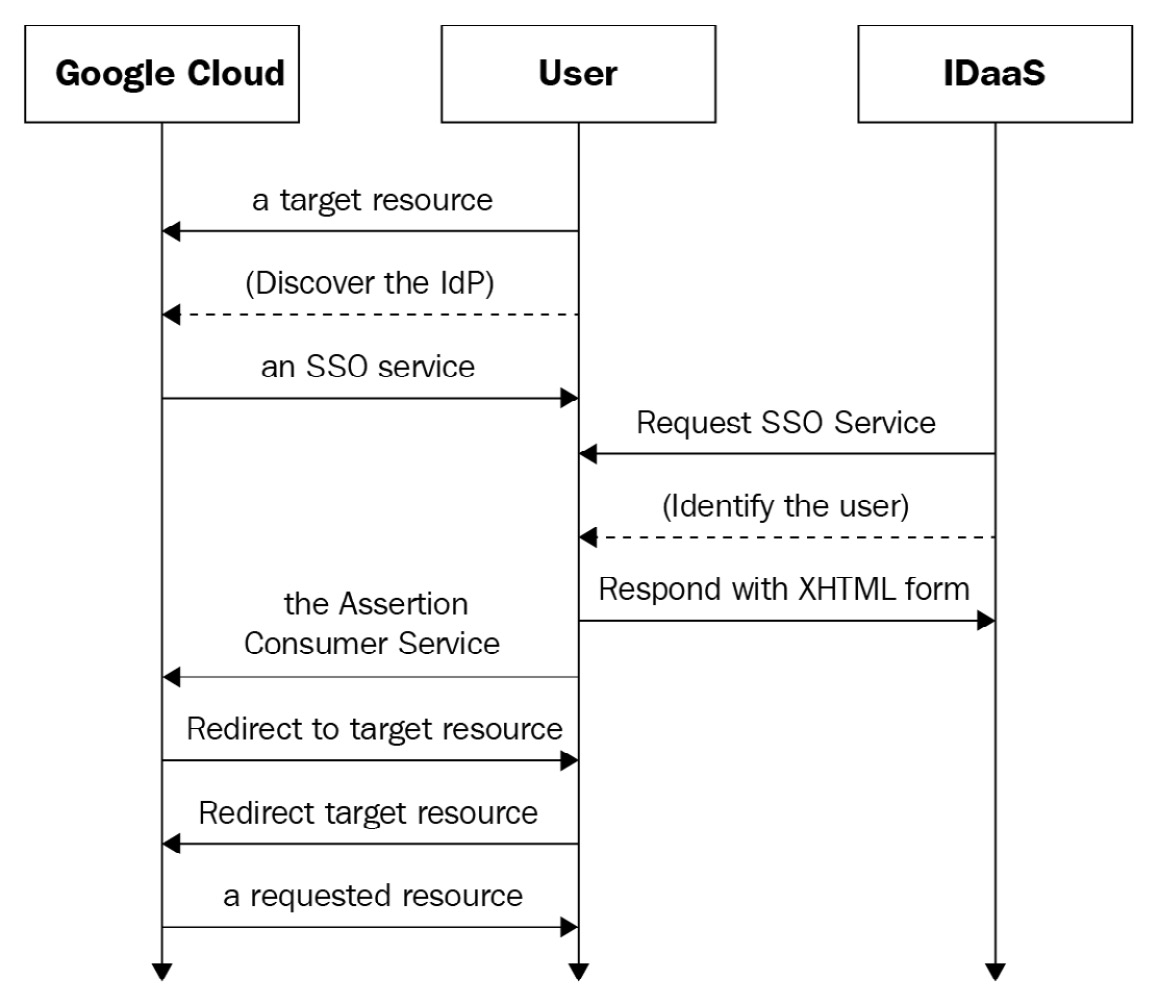

Behind the scenes, SAML works like this:

Figure 2.6 – SAML authentication

This is what the login process will look like to a user (SAML):

- You follow a link to a protected resource, say Google Cloud Storage.

- The browser gets redirected to the IDaaS provider.

- If you aren’t already authenticated, you log in at the SSO service, just like you do for everything else.

- The provider passes a SAML response back through the browser to Google’s Assertion Consumer Service (ACS). The ACS makes sure that the response is appropriate, figures out which user you are, and then Google Cloud IAM decides whether you have access to the individual resource you requested. If you do, you get access to Cloud Storage.

This all sounds good, but what if that third-party service is Microsoft’s AD? Well, that’s a different kettle of fish.

Integrating Cloud Identity with Microsoft AD

I read a study once that said something like 95% of Fortune 500 companies use Microsoft AD as their primary IdP. So, chances are, if you’re part of an established organization, you’re probably doing your user identity management and your login through AD. How can Google Cloud integrate with an existing AD environment? There are four main ways, and I want to take time to explore each. Let’s start with the two least commonly used options.

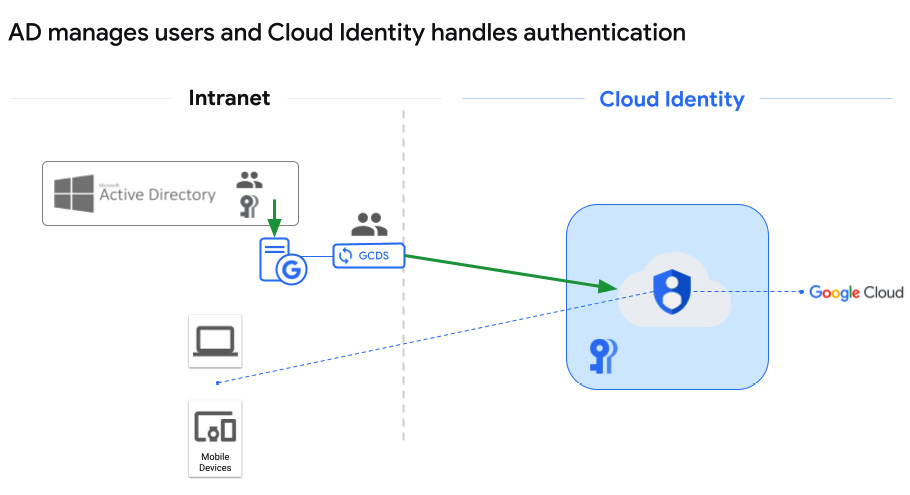

AD manages users and passwords on-premises, users are replicated to Google, and Cloud Identity then acts as the IdP for access to Google Cloud

This is probably the most simplistic form of AD integration. You let AD manage the users on-premises and use an automated tool from Google called Google Cloud Directory Sync (GCDS) to synchronize that user list with Google Cloud. Once Google Cloud Identity gets the user list, then users can log in and set up new passwords for use in Google Cloud. To be clear, this approach means that users have one username and password for everything on-premises, and then they will use the same username with a separate password to log into Google Cloud through Cloud Identity.

GCDS is software that you can download from Google: https://tools.google.com/dlpage/dirsync/. You provide a Windows or Linux server in your on-premises environment, install the software, connect it to Cloud Identity on one side using a new Cloud Identity superuser account (just used for GCDS), and connect it to AD using an account with minimal read-only permissions on the other. Then, you can use a User Interface (UI)-driven tool called Configuration Manager to set your configurations and let them run.

With GCDS, you can control the following:

- Synchronization frequency.

- Which part of your user domain gets synchronized, and within that, use rules to fine-tune the details.

- What user profile information will be passed to Cloud Identity when synchronization occurs.

All the data is passed to Google Cloud encrypted end to end. For more details, visit: https://support.google.com/a/answer/106368. Architecturally, this would look like the following figure:

Figure 2.7 – AD manages users and Cloud Identity handles authentication

This is when you should use it:

- When you already have AD configured on-premises and the users who need to access Google Cloud are in it. So, AD is the one source of truth for which users exist, along with their group memberships, organizational structure, and so on.

- You are looking for the simplest AD to Cloud Identity integration, possibly because only a small subset of your users require Google Cloud access.

- You may want the Google access and IdP kept separate and external to your organization.

- You may be experimenting with integration and aren’t ready to go all in just yet.

This is what the login process will look like to a user (as with any of the options using Google as the IdP):

- The user follows a link to a protected resource, such as Google Cloud Storage.

- Google recognizes the user because GCDS populated the user list. The user is redirected to a standard Google sign-in screen where they enter their standard username and Google Cloud-specific password. If 2SV is enabled, they are prompted to provide their key or code.

- If the user authenticates, then IAM decides whether they are authorized to access the requested resource, and if so, they are then redirected back to the service they requested – in our example, Cloud Storage.

The issue here is the two sets of passwords. Even if a user manually sets them both to the same value, they aren’t managed in a single place. If you need to update your password, you’d have to do that in AD and then again in Google Cloud Identity. In some cases, this approach can allow for better separation between your on-premises environment and Google Cloud, but it’s also one more password to manage for your users.

If passwords being the same is your only worry, then you could synchronize them too.

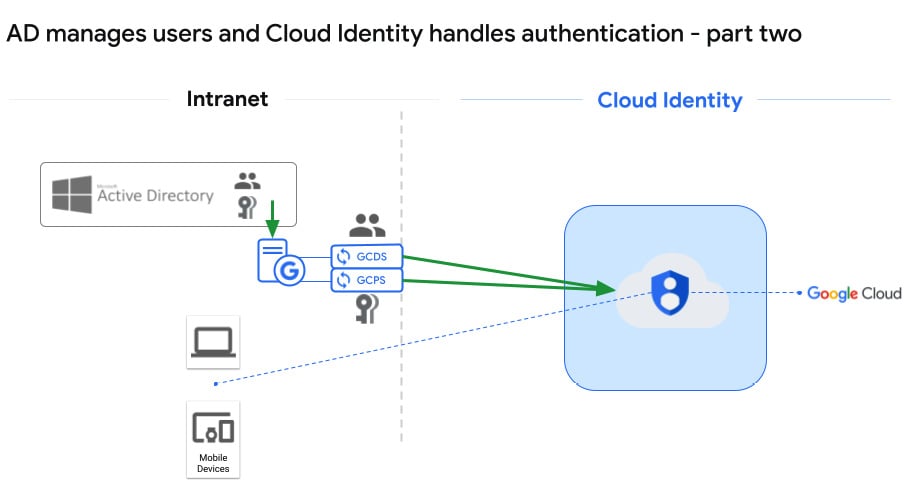

AD manages users and passwords on-premises, users and passwords are replicated to Google, and Cloud Identity then manages access to Google Cloud

This is a slight variation on the last option. Here, you are still using GCDS to sync the users, but you’re adding a separate application from Google to your on-premises environment, Password Sync: https://support.google.com/cloudidentity/answer/2611842. The nice thing about Password Sync is that it auto-syncs the passwords the moment the user or admin changes them in AD. The concern with Password Sync is that it’s pushing all the passwords to Google. I know it’s encrypted, Google-secured, and all that good stuff, but just the idea makes me a little nervous.

It looks like this:

Figure 2.8 – AD manages users and Cloud Identity handles authentication – part two

This is when you should use it:

- When you already have AD configured on-premises and all the users who need to access Google Cloud are in it.

- You are looking for a basic AD to Cloud Identity integration, possibly because only a small subset of your users need Google access.

- You want the Google IdP part kept separate and external to your organization.

- You may be experimenting with integration and aren’t ready to go all in just yet.

This is what the login process will look like to a user:

- The user follows a link to a protected resource, such as Google Cloud Storage.

- Google recognizes the user because GCDS populated the user list, and this time, Password Sync provided the password. The user is redirected to a standard Google sign-in screen where they enter their username and password.

- If the user authenticates, then IAM decides whether they are authorized to access the requested resource, and if so, they are then redirected back to the service they requested – in our example, Cloud Storage.

Now that we have those two options out of the way, let’s talk about the two most commonly used ways to integrate AD with Google Cloud.

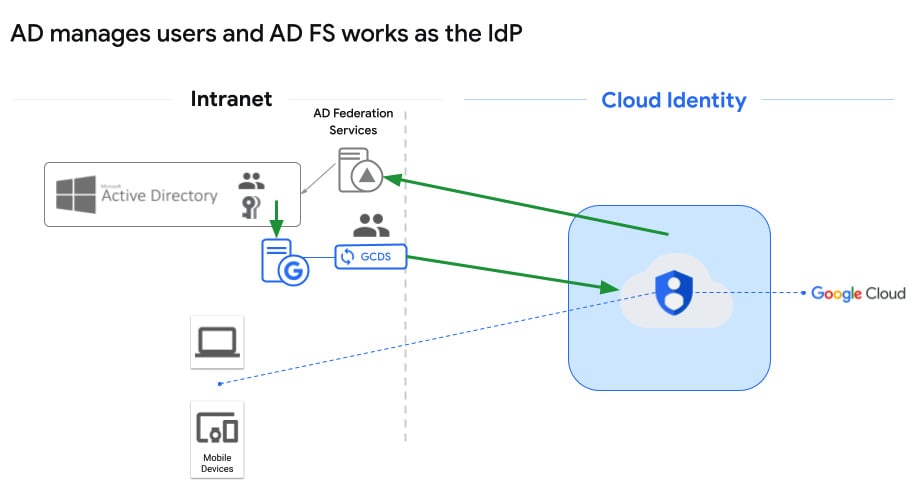

AD manages users and passwords on-premises, users are replicated to Google, and Cloud Identity uses on-premises AD FS SSO for authentication

That’s a mouthful, but it’s easier than it sounds. This option starts like the last two – you download, set up, and configure GCDS. It focuses on what it’s good at – replicating user information out of AD and into Google Cloud Identity. The big addition to the on-premises picture is Active Directory Federation Services (AD FS), which is a Microsoft SSO solution. So, Google knows you’re a user because GCDS replicated your user information into Cloud Identity, but the authentication is redirected back on-premises, where it’s handled by AD FS. It looks something like this:

Figure 2.9 – AD manages users and AD FS works as the IdP

This is when you should use it:

- When you already have AD configured on-premises and the users who need to access Google Cloud are in it.

- You already have or are willing to set up AD FS to facilitate an on-premises SSO solution.

- You are looking for an AD-based solution where there aren’t separate passwords for the different environments, and you don’t want the passwords to be synchronized.

- You want to integrate Google into your existing AD FS SSO environment.

This is what the login process will look like to a user:

- You follow a link to a protected resource, such as Google Cloud Storage.

- If you are already authenticated into your on-premises AD environment, then SSO authenticates you behind the scenes. If not, then Google will redirect you to the AD FS authentication portal, as configured in your on-premises environment.

- Once you have authenticated, Google Cloud IAM will determine whether you can access the protected resource. If so, you are then automatically redirected to the originally requested resource – in our example, Cloud Storage.

As you might imagine, the devil tends to be in the details. For in-depth coverage of federating with AD, as we’ve seen in this section, take a look at https://cloud.google.com/architecture/identity/federating-gcp-with-active-directory-introduction.

Unfortunately, any of these options which depend on GCDS, may run into issues when migrating some of the accounts to Google.

GCDS challenges

Have you ever signed up for a Google-owned service using your work email address as your username? Perhaps before the organization decided to use Google Cloud, you created a trial account, or maybe you signed up for Gmail using your work email as a secondary address? I’ll lay odds that if you haven’t, someone else in your organization has, and to make matters worse, they may not even work for you anymore.

When it comes to Google, there are two types of accounts – managed and consumer. Managed accounts are fully managed by an organization, through Cloud Identity or Google Workplace, such as my gcp.how. Consumer accounts are owned and managed by the individuals who created them, and they are used to access general Google services such as YouTube or Google Cloud.

There are several possible issues here, depending on the exact circumstances. For a full discussion, see https://cloud.google.com/architecture/identity/assessing-existing-user-accounts. I’m going to look at just a couple.

In our first pain-point example, Bob signs up for an account in Google Cloud and uses his [email protected] corporate email address as his username. gcp.how has decided to move forward and create an IT presence in Google Cloud, with Cloud Identity acting as the IdP. You’re in the process of setting up GCDS and you’re working on the users you’re going to migrate. Bob has an account in AD tied to [email protected], but Google already knows Bob as [email protected] through the consumer account he created when he signed up as an individual GCP user.

The solution here isn’t too bad. First, make sure you add and validate any variations of your domain name to Cloud Identity so that it knows about them. So, if gcp.how is your main domain but your organization also sometimes uses gcp.help, then add them both to Cloud Identity, with .how being the primary. Next, Cloud Identity has a transfer tool you can access (https://admin.google.com/ac/unmanaged), which allows you to find employee accounts that already exist as consumer accounts. You might want to download the conflicts and reach out to them yourself before initiating the transfer so that they can watch for the transfer request email and know what it is (not spam!) before it arrives. When ready, the Google transfer tool can send a transfer request to the user. When they accept, their account then moves from consumer to managed, and it falls under the control of the organization. For more details, visit https://cloud.google.com/architecture/identity/migrating-consumer-accounts.

Another variation on this same theme relates to former employees. Before gcp.how decided to move to Google, Malo used to work for them, but he left after some unpleasantness. Before he left, he was doing some experimentation with a private Google Cloud account tied to his email address, [email protected].

Now, the Cloud Identity transfer tool doesn’t locate conflicting user accounts because they are in AD; it locates them because they are tied to a particular domain. You see the malo@ account and, after a little research, you realize that he no longer works for gcp.how. A real concern here is that since he has an account in Google Cloud tied to a gcp.how email address, he might try a form of social engineering attack, perhaps by requesting access to a corporate project, and hey – the request is associated with a gcp.how account, right?

This is a pain point. In this case, you should evict the [email protected] consumer account. The steps aren’t bad and details can be found here: https://cloud.google.com/architecture/identity/evicting-consumer-accounts. Essentially, you create an account directly in Cloud Identity using the conflicting [email protected] email account. You’ll get a warning prompting you to ask for a transfer or to go ahead and create a new user. Create the new user with the same email address, and then immediately delete it. By purposefully creating a conflict and then deleting it, you will trigger an automated Google process that will force the existing [email protected] account to change its credentials.

There are a few more pain points related to individuals using Gmail accounts for personal and corporate purposes, such as accessing documents and individuals who might use their work email address as an alternative email address on a Gmail account. These may be harder to troubleshoot, and details on handling these situations and more can be found here: https://cloud.google.com/architecture/identity/assessing-existing-user-accounts.

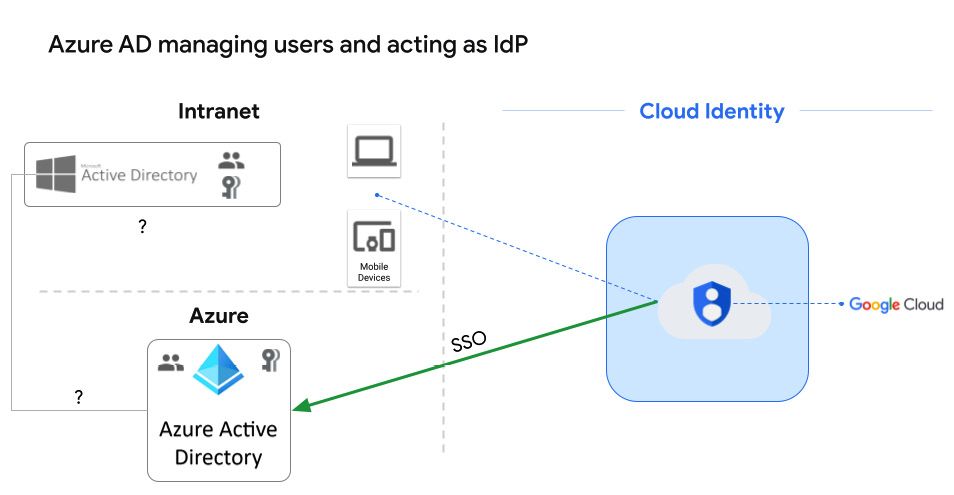

The final AD-related user and identity solution that I’d like to discuss is Azure AD.

Cloud Identity delegates all IdP and user services to Microsoft’s Azure AD

There are a couple of reasons you might fall into this category. You may have moved some or all of your on-premises authentication into Azure as part of another cloud initiative, or you may still have on-premises AD, but at some point in the past, you set up federation from your on-premises AD instance to Azure AD. If this is the case, then Cloud Identity can pass the responsibility for all user management and IdP services to Azure AD:

Figure 2.10 – Azure AD managing users and the IdP

For details on Azure AD federation, visit https://cloud.google.com/architecture/identity/federating-gcp-with-azure-active-directory.

This is when you should use it:

- You already have, or are planning to implement, Azure AD as your authoritative SSO service.

- You want to provide a seamless SSO experience to your users across the on-premises, Azure, and GCP environments. Even AWS can sync with Azure AD.

- You would prefer your SSO service to be managed by Azure AD, rather than setting up and managing it yourself in AD FS.

This is what the login process will look like to a user:

- You follow a link to a protected resource, such as Google Cloud Storage.

- If you are already authenticated into your Azure AD environment, then SSO authenticates you behind the scenes. If not, then Google will redirect you to the Azure AD authentication portal and you will log in there.

- Once you have been authenticated, Google Cloud IAM will determine whether you can access the protected resource. If so, you are then automatically redirected to the originally requested resource – in our example, Cloud Storage.

At this point, I’m going to assume that you’ve decided how you want to manage your users, what your IdP will be, and that you’ve created, or linked up at the very least, an initial set of key users. What constitutes a key user? Well, I’m about to tell you about a starter set of security groups that you need to create in Google Cloud. After I do, come back here and see whether you can find at least one user who would fit into each of those security groups.

Creating an initial set of security groups

Before we get to creating an initial set of groups and assigning users to them, let’s have a quick side discussion on two security-related concepts – the principle of least privilege and Role-Based Access Control (RBAC). These aren’t groundbreaking concepts to anyone familiar with security, but they are still worth mentioning.

The principle of least privilege is simply common sense – don’t give users permissions that they don’t need to do their jobs. If you work or have worked in an office building, then your swipe or key probably doesn’t open every door in the building. Why? Because most jobs don’t require a person to access more than a few specific building areas. If you’re part of building management, security, or maintenance, then you might need unfettered access, but those are a handful of specialized positions, not average workers. Why not let everyone access everything? Because you’re likely to get robbed if you do.

The same logic applies to Google Cloud. Remember in the previous chapter, when I talked about the huge list of services that Google Cloud offers? Well, you or someone in your organization is going to have to put in some time learning about how IAM security settings work in Google, and then research exactly what different roles in your organization need in terms of GCP access. We will discuss access control and IAM configurations in Chapter 5, Controlling Access with IAM Roles.

RBAC essentially says that when it comes to assigning security, think job roles instead of individuals. You might be your own special snowflake, but your job likely isn’t. Most people are one out of a set of employees who perform a similar job function within the organization. So, instead of setting security for developer Bob directly, and then turning around and implementing the exact same security settings for developer Lee, put Bob, Lee, and the other developers on team six in the dev-team-6 group, and set permissions for the group as a whole. It makes long-term management of security settings a whole lot easier. You’ve hired a new developer, Ada, into development team six? Just add her to the group, and bam – she gets the exact permissions she needs.

As far as the initial set of Google Cloud groups goes, Google recommends you start with six and that you eventually identify at least one initial user who you can slot into each. At this point, these groups won’t have the Google Cloud IAM access settings to perform the jobs being proposed, but we will add that in a later chapter. Also, there’s nothing that says you must use these exact groups, so feel free to tweak this initial list any way that you need. If you are looking for the wizard in Google Cloud to give you a nice green checkmark for completing this step, then you’ll have to create at least the first three:

gcp-organization-admins: Here will be your Google Cloud organization administrators, with full control over the logical structure of your organization in GCP. These are super-users, and there won’t be many. gcp-network-admins: This will be your highest-level network administrators. These are the people who, among other things, can create VPC networks, subnets, control network sharing, configure firewalls, set routing rules, and build load balancers. gcp-billing-admins: Someone needs to be able to view and pay the bills, right? At least they do if you want to keep the Google Cloud environment lights on. There also needs to be someone who pays attention to your level of spending.gcp-developers: Ah, this is my old job. Here’s where you’ll put your top-level developers, who will be busy designing, coding, and testing apps in Google Cloud.gcp-security-admins: The core security-related people, with top-level access to set and control security and security-related policies across the whole organization. gcp-devops: Lastly, here you have your highest level of DevOps engineers, responsible for managing end-to-end continuous integration and delivery pipelines, especially those related to infrastructure provisioning.

Again, this list of initial security groups is in no way designed to be exhaustive or mandatory; it’s just a nice place to start. If there are other high-level groups that would aid your organization in some way, you can add them now or at any time.

Now that you have a plan for your initial set of security groups, let’s create them in Google Cloud. You can either use Google’s new foundation wizard to create these groups (https://console.cloud.google.com/cloud-setup/users-groups) or you can manually create them yourself, perhaps adding a few groups that you’ve included in your plan. Here’s how:

- Log in to Google Cloud Console (https://console.cloud.google.com/) using your Cloud Identity super admin account created earlier in the chapter. If you followed my naming recommendation, then it’s something like

gcp-superadmin@<your-domain>.

- Navigate to Navigation menu | IAM & Admin | Groups. The direct link is https://console.cloud.google.com/iam-admin/groups.

- At the top of the page, click Create.

- Provide a group name from your initial list; I’d recommend using the same name as the prefix for the group email address. That’s why all the suggested group names are email address-friendly. If you want to, add an appropriate description.

- Save.

- As soon as you save the group, the Group Details page for the new group will appear and show you as the only current member. You should be logged in as the first organization admin and as the group creator; that account automatically becomes the owner of the group.

- Use the Add Members button at the top of the page and add any users you have identified as members of this group.

- Repeat steps 1–7 until you have your initial set of groups created.

Very nice. At this point, you have your IdP and the user management figured out and set up, and you’ve created an initial set of high-level groups in Google Cloud, with a corresponding user or two in each. When ready, move on to step 3 and set up admin access to your organization.

Free Chapter

Free Chapter