Environments are used to describe a general deployment target such as development, test, staging, or production. You can protect environments with protection rules, and you can provide configuration variables and secrets for specific environments.

Getting ready

We will first create some environments using the web UI and add some protection rules, secrets, and variables. Then, we add them to our existing workflow.

How to do it…

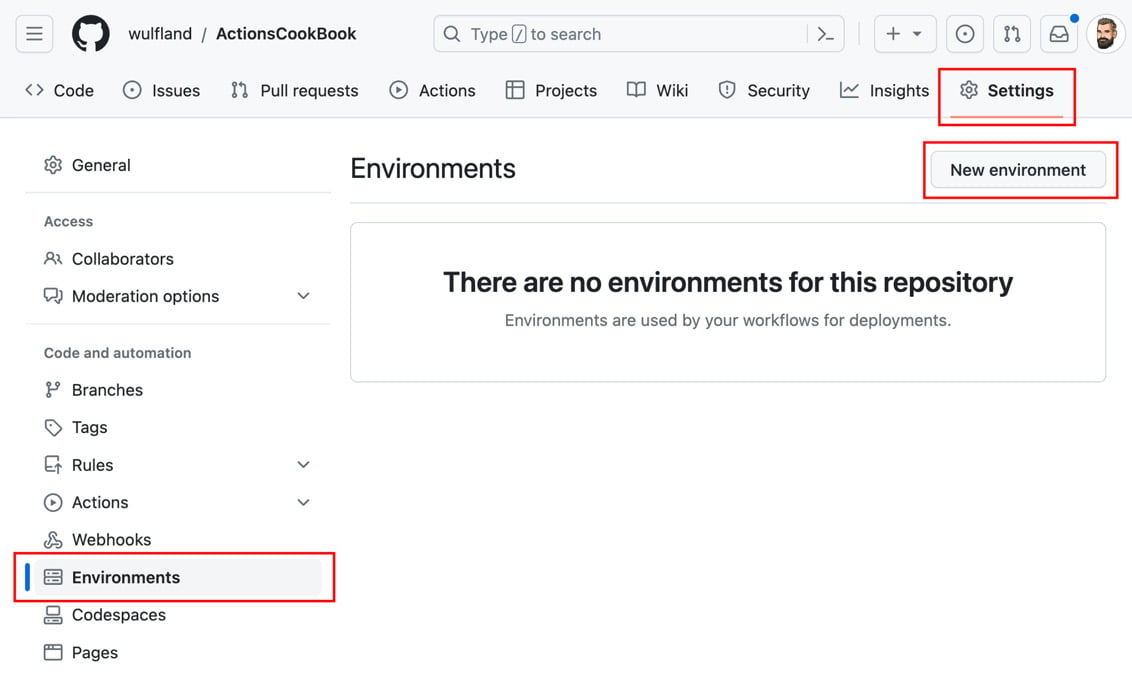

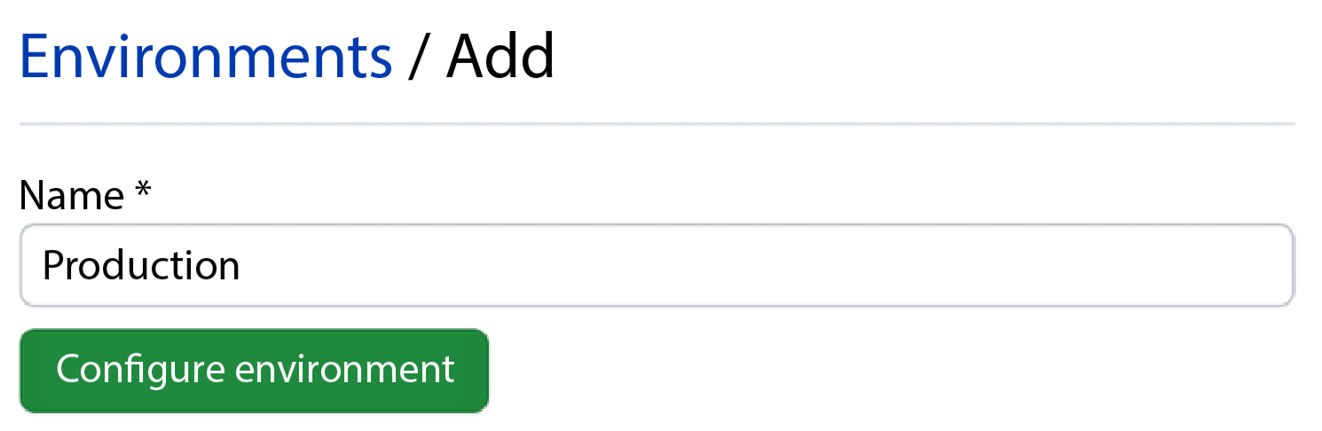

- Navigate to Settings | Environments and click on New environment (see Figure 1.25):

Figure 1.25 – Managing environments in a repository

Enter the name Production and click Configure environment (see Figure 1.26):

Figure 1.26 – Creating a new environment

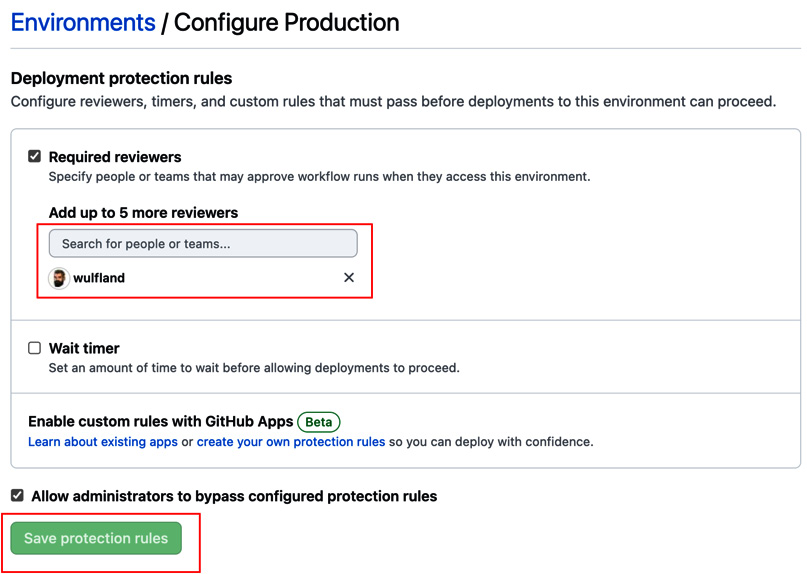

- Add yourself as a required reviewer and click Save protection rule (see Figure 1.27):

Figure 1.27 – Configuring deployment protection rules

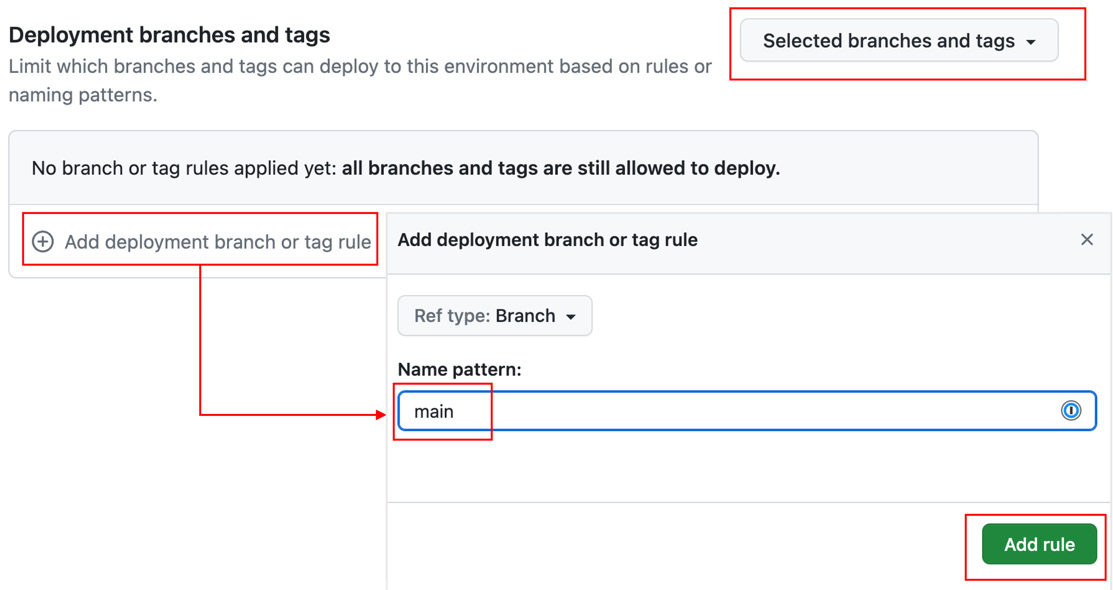

- Under Deployment branches and tags, choose Selected branches and tags, click the plus symbol, and add a name pattern for the

main branch (see Figure 1.28):

Figure 1.28 – Configuring deployment branches and tags

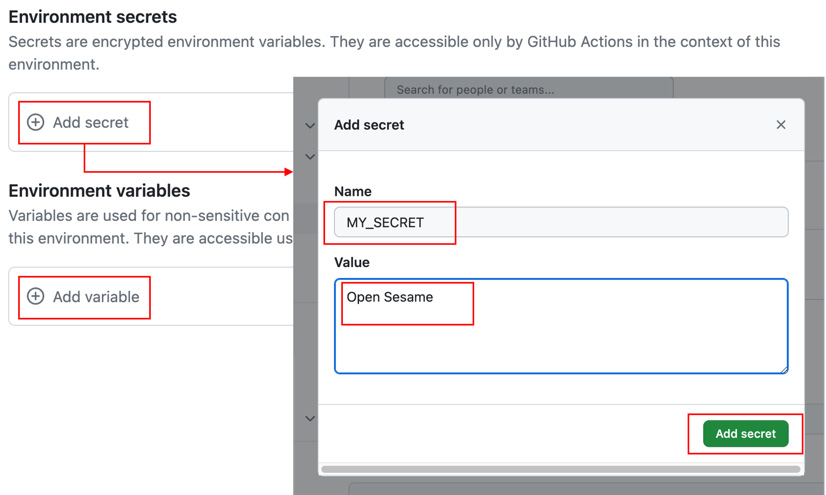

- Under Environment secrets, click on Add secret and add a new

MY_SECRET secret with the value Open Sesame (see Figure 1.29). Repeat this with Add variable and add a WHO_TO_GREET variable with the value Production users:

Figure 1.29 – Adding secrets and variables to environments

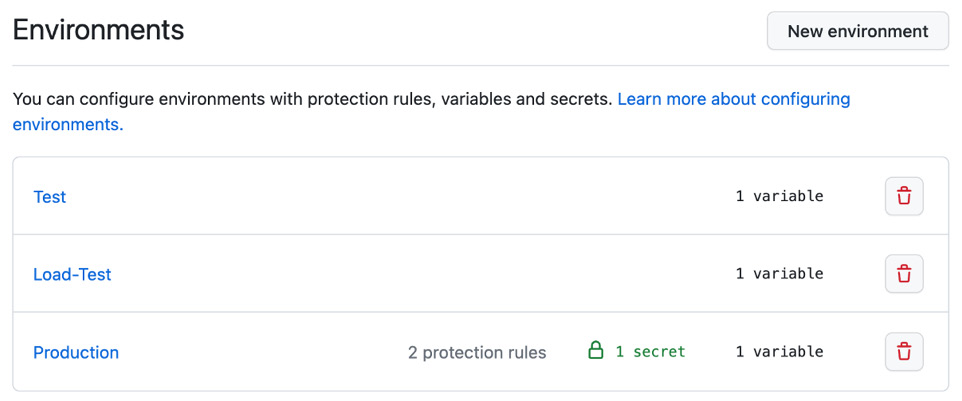

- Repeat step 1 and create two additional environments,

Test and Load-Test. We will use these environments in the next steps to show how to execute jobs in parallel. You don’t have to configure deployment branches or required reviewers. Just add a WHO_TO_GREET variable with the corresponding value. The result should look like Figure 1.30:

Figure 1.30 – Multiple environments in the settings of the repository

- Now, go back to the workflow file and edit it. Add a new job beneath

first_job called Test that runs on the latest Ubuntu image. We associate this job with the Test environment. To run this job after first_job, we use the needs property and set it to the job we depend on:Test:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

environment: Test

needs: first_job

To see how secrets are overwritten by the environment, we have to use a little hack. As GitHub searches for the value of secrets in the output of the log to mask it, we have to modify the actual text. We can do this, for example, using the sed 's/./& /g' command. This will add a blank between every character of the secret. With this little hack, the steps of the Test job should look like this:

steps:

- run: |

echo "Hello ${{ vars.WHO_TO_GREET }}  from ${{ github.actor }}."

sec=$(echo ${{ secrets.MY_SECRET }} | sed 's/./& /g')

echo "My secret is

from ${{ github.actor }}."

sec=$(echo ${{ secrets.MY_SECRET }} | sed 's/./& /g')

echo "My secret is  '$sec'."

'$sec'." - Next, add a new

Load-Test job that is associated with the Load-Test environment and also executes after first_job:Load-Test:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

environment: Load-Test

needs: first_job

Just copy the steps from Test. There is no need to change anything.

- The last job is a

Production job. In addition to the name, the environment property accepts a URL that later will be displayed in the workflow designer. Set it to any URL you want. To show how after a parallel execution of jobs the workflow can merge again, we will run Production after Test and Load-Test:Production:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

environment:

name: Production

url: https://writeabout.net

needs: [Test, Load-Test]

Just copy the steps from the previous jobs.

- Commit your changes to the

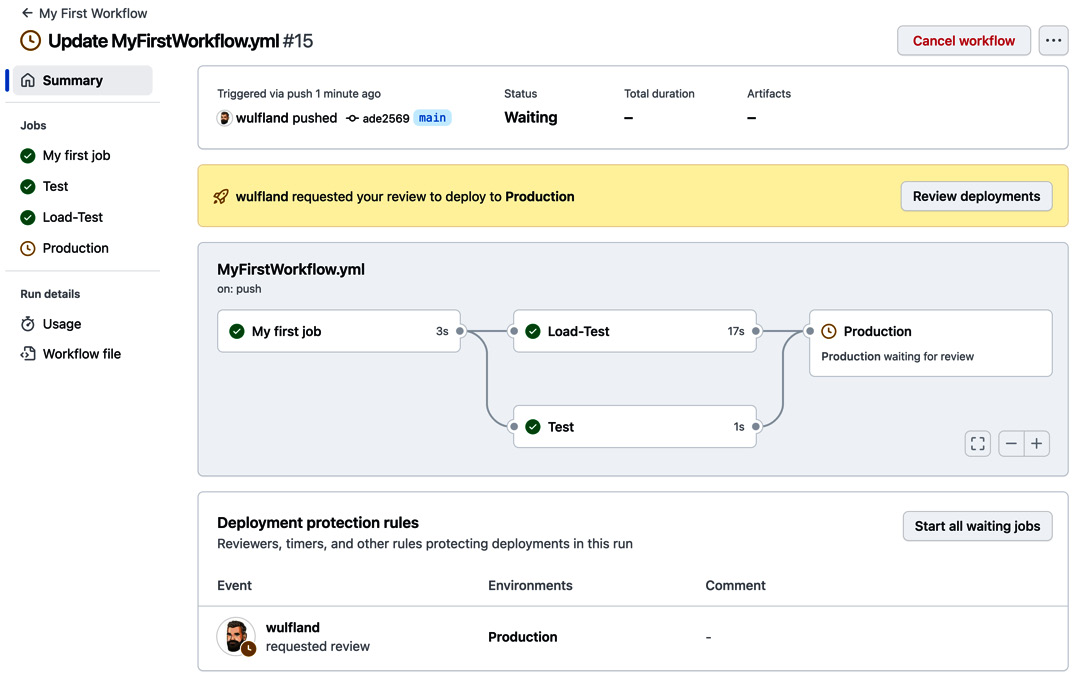

main branch. The workflow will run automatically. Navigate to the new workflow run and inspect the workflow designer, which nicely shows the parallel execution. The workflow will pause before executing Production and will wait for approval (see Figure 1.31):

Figure 1.31 – The workflow will stop before an environment with required reviewers and wait for approval

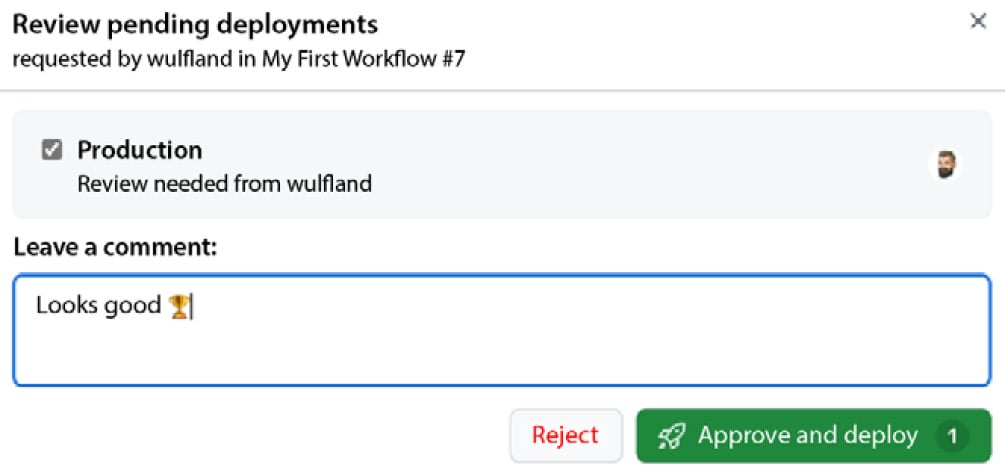

- Click Review deployment, check Production, and add an optional comment. Click Approve and deploy to start executing the

Production job (see Figure 1.32):

Figure 1.32 – Approving a protected environment

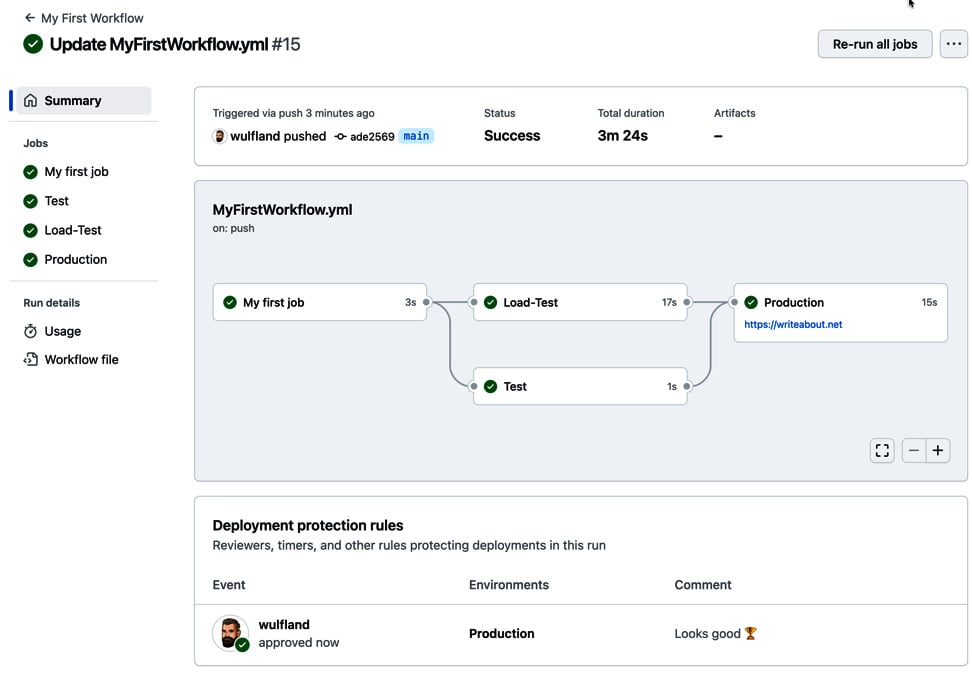

The workflow will execute completely, and the result should look like Figure 1.33. Note that the URL is displayed in the Production environment. Also, note the history of approvals in the workflow summary:

Figure 1.33 – The final summary of the workflow

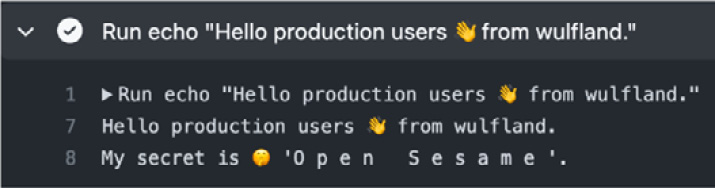

Open the individual jobs and inspect the output of the step we added (see Figure 1.34). The secrets and variables are used from the repository and are only overridden if we set them in an environment:

Figure 1.34 – The production secret is only available to the production environment after approval

There’s more…

If you are setting secrets or variables for an environment using the GitHub CLI, then you can specify them using the --env (-e) argument. For organization secrets, you set the visibility (--visibility or -v) to all, private, or selected. For selected, you must specify one or more repos using --repos (-r):

$ gh secret set secret-name --env environment-name

$ gh secret set secret-name --org org -v private

$ gh secret set secret-name --org org -v selected -r repo

Environments have more options than we have used in this recipe. You can also configure a wait timer that will pause the workflow for n minutes (with a maximum of 30 days) before executing the deployment job for that particular environment.

There is also a new feature called custom deployment protection rules that is still in beta. This feature allows the creation of GitHub apps that can pause your deployment and wait for a specific condition. There are already apps from Datadog, Honeycomb, Sentry, New Relic, and ServiceNow (see https://docs.github.com/en/actions/deployment/protecting-deployments/configuring-custom-deployment-protection-rules#using-existing-custom-deployment-protection-rules). We’ll have a closer look at custom deployment rules in Chapter 7, Release Your Software with GitHub Actions.

The true power of environment protection rules lies in the deployment branch or tag rules. This can restrict code that does not apply to branch protection rules from deploying to certain environments. This can include all kinds of checks – Codeowners approvals, code reviewers, deployments to certain other environments, SonarQube quality gates, and many other automated code checks (see https://docs.github.com/en/repositories/configuring-branches-and-merges-in-your-repository/managing-protected-branches/about-protected-branches for more information).

Free Chapter

Free Chapter

from ${{ github.actor }}."

sec=$(echo ${{ secrets.MY_SECRET }} | sed 's/./& /g')

echo "My secret is

from ${{ github.actor }}."

sec=$(echo ${{ secrets.MY_SECRET }} | sed 's/./& /g')

echo "My secret is  '$sec'."

'$sec'."